The first day of class in a new job or with a new set of students is always daunting. And while first-day nerves are natural, the pressure is magnified when teaching in a different country or cultural environment.

When I first started teaching at the university level in China, I’d already lived in the country for several years and was lucky to have great institutional support in developing my pedagogical skills, but I still made many mistakes.

(For example, in my first class I assigned my freshmen students – the vast majority of whom did not know what an academic journal was – journal articles as reading, but failed to explain the concept of an academic paper or guide them on how to read one effectively. The result: stressed, tired, and confused students who tried to memorize the entire contents of the articles!)

With hindsight, I wish I’d reached out more for specific advice to help me adapt from the beginning. However, I quickly learned that there are simple steps you can take to tailor your syllabi, classroom management, and teaching methods to succeed in China. Here’s my top five:

1. Put Clear, Fair Grading Rubrics in Your Syllabus

It’s cliched but true to state that Chinese students are (in general) very grade-oriented. And, in a diverse classroom with both Chinese and international students (as in many joint venture and top universities in China), this tends to rub off on non-Chinese students so that everyone is competing for top grades.

Various methods, from moving away from grades altogether (“ungrading”), to contract-based grading (where students decide their contribution in advance and receive the grade they select so long as they deliver on their commitment), have been put forward to alleviate grading anxiety.

However, I favor the simplest approach: clear grading rubrics that explain to students exactly how they will be assessed. In my experience, in Chinese universities students expect (and mostly want) to be graded, and rubrics help to make the process fair and transparent, and mean students do not need to try to read their instructor’s mind to guess at the grading process.

It’s best to put these on the syllabus from the beginning (or on the course site, with a link in the syllabus), not only to make them easy for students to find, but because the syllabus serves as your contract with your students, and you can point to it in the event of any future grading disputes.

(Do you need support creating tailor-made rubrics for your courses? Reach out to me for help today).

2. Learn Students’ Names with Name Cards and Online Introduction Forums

One of the wonderful things about teaching in China is that students really respect and want to bond with their instructors. As a result, learning their names, hometowns, academic interests, and other details about their lives helps hugely in creating a learning environment based on connection and trust, and opening up dialogue between students and faculty.

However, it can be difficult for non-Chinese instructors to be faced with unfamiliar sounding names and terms (even as a Mandarin speaker I struggle sometimes). Luckily, there are two super simple practical ways to learn your students’ names and other details quickly.

First, ask your students to make name cards using paper and a thick marker pen (a normal ballpoint pen will be too small, rendering your name cards useless), and put them on the desk in front of them during class. This might seem a bit weird at first, but it really is the best and easiest way to learn your students’ names without interrupting the class discussion constantly to clarify someone’s name.

(And don’t forget to make a name card for yourself so that students can learn your name easily too.)

Second, before or during the first week of class, ask students to introduce themselves on an online forum (most university Learning Management Systems have a “Forums” tool or similar functionality). Model an introduction by telling them about yourself, your academic interests, where you’re from, and some kind of ice-breaking fact about you. Include a picture, and ask your students to do the same. That way, the forum serves as a record that you can use to refresh your memory about your students throughout the course.

In fact, students also appreciate name cards and introduction forums because it helps them connect with their classmates more quickly and easily (after all, for students university is also social experience – they want to meet new people, and appreciate a helping hand in doing this).

3. Explain the Importance of Genre

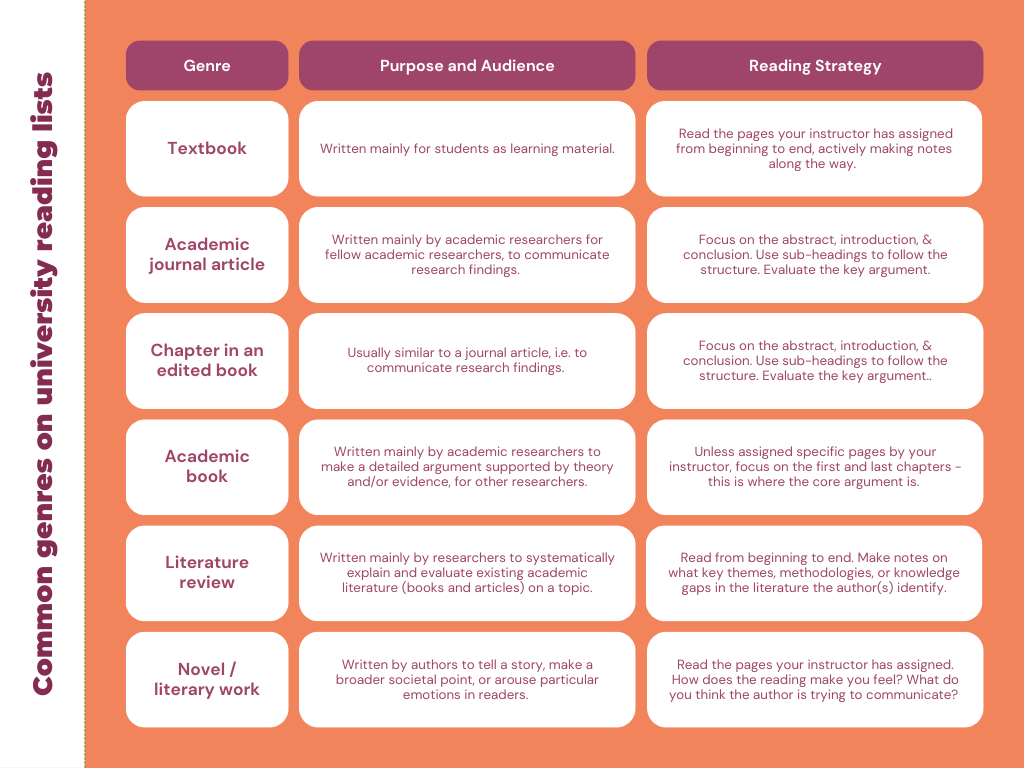

Almost all university courses involve some kind of reading material. Students coming from Chinese high schools are usually very familiar with how to read and learn from a textbook (or enjoy a novel), but not academic articles, research proposals, or academic books and book chapters.

If you have first (and even second) year students in China (or Chinese students in your classroom overseas) and you are assigning these types of readings to your students, take the time to explain:

- What different types of materials aim to do and for whom. For example, tell them that a journal article aims to communicate research findings to other researchers. (My students are usually shocked to learn that other faculty – and not students – are the primary audience for many of their readings).

- How to read different types of materials efficiently (e.g. for academic writing, focus on the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, and do not try to memorize everything).

- Why they have been assigned specific materials – i.e. is it to learn about a set of theories or facts, evaluate the authors’ argument, and/or to understand and apply research methodologies?

(Feel free to use this table in your teaching, but don’t forget to attribute it to Discovery Hub.)

Because they haven’t been exposed before, they need someone (i.e. you!) to teach them these things. Understanding what they’re reading and why results in much happier, more productive, and more engaged students.

Check out this blog post on China’s gaokao exam to better understand your Chinese students’ high school experiences.

4. Use Anonymous Polls and Think-Pair-Share to Get the Conversation Started

It is another somewhat true cliche that Chinese students are less used to speaking up in class than students from places like the US or UK. However, research clearly shows that active learning in which students participate in class rather than passively listening to a lecturer improves both learning outcomes and student well-being.

Luckily, there are several techniques you can use to get your students more comfortable with actively participating in class discussion.

For example, I love using PollEverywhere to gather students’ thoughts, feedback, and opinions in an anonymous, low stakes way (students can simply scan a QR code and respond to a prompt online, and PollEverywhere will create an instant visualization of what students think about a particular topic or question).

Once they see what their classmates think via the poll, students are more keen and comfortable to respond verbally (and you can also ask students if they agree or disagree with the majority opinion and why).

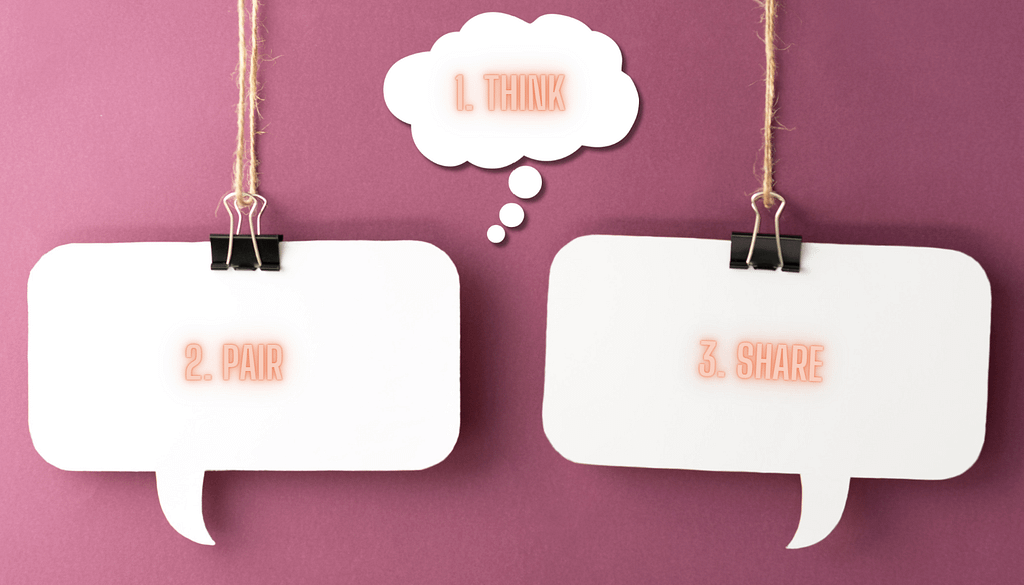

Another simple technique I use is “Think-Pair-Share”. This involves (1) giving students one minute or so to consider their response to a prompt; (2) a few minutes to discuss with a partner; and (3) a whole class group sharing session in which they share their or their partner’s thoughts with the whole class.

Think-Pair-Share allows students to gather their thoughts slowly (which is particularly important if English is not their first language) and build up to the whole class discussion. As a result, students experience less pressure and make more well-thought out contributions.

(Tip: liven things up by enforcing time limits using this explosion-themed 1 minute YouTube timer.)

5. Enforce Diversity in Group Work (and Don’t be Afraid to Break Up Cliques!)

Relatedly, group activities and projects are a great way to get students learning actively and build teamwork and leadership skills as well as subject-specific knowledge.

However, especially in classrooms with a mix of Chinese and international students, it’s natural for students to group together with people from the same country or with other shared characteristics (for example, students from the same province, or with the same gender or major choose to work with each other if given the opportunity).

In doing this, they miss out on the chance to develop their cultural intelligence and work in diverse teams. The best way to avoid this is simply to assign groups yourself, either randomly or by proactively mixing different people together.

(I have forced my students to physically get up and move tables – sometimes they grumble at first, but they always appreciate the chance to move and talk to different people afterwards.)

Indeed, from 1:1 conversations with students and through reading comments in my teaching evaluations, I’ve learned that most of them actually want to work with more diverse groups, but it’s simply socially awkward not to sit beside and partner with their existing friends.

(Thinking back to my own student days, I definitely would have found it hard to plonk myself on to a table with a bunch of strangers when my friends were already in the room!)

By enforcing diverse groups, you’re actually doing your students a social favor as well as helping them learn.

Conclusion

Teaching university students in China is a joy and a privilege. However, it’s important for international instructors to adapt their teaching and class management to create a more inclusive, happier, and productive classroom environment.

Luckily, by following these simple steps, you’ll be well on your way to success.

Would this article be helpful for someone you know? Click the links below to share ⬇

Check out more tips for academic success by following Discovery Hub on social media ⬇

Copyright @ 2024 Discovery Hub Educational Consulting (Suzhou) Ltd 探索枢纽教育咨询(苏州)有