Cultural intelligence, i.e. the ability to succeed in different cultural settings and communicate across diverse groups of people, is increasingly recognized as a critical skill for educators teaching students from different backgrounds.

I came face to face with its importance in one of my first classes as a new faculty member in China. In an effort to connect with my students by learning their names quickly, I’d distributed the classroom’s (blue and red) marker pens and asked them to make name cards. Confusingly, awkward silence descended.

At the end of the class, a student nervously approached me and told me that writing one’s name in red ink is considered a signal of imminent death in Chinese culture, as it was the color historically used to sign execution warrants.

After (at that point) half a decade in the country, I couldn’t believe I’d made such a insensitive mistake. However, it was also an important lesson for me in how critical cultural intelligence is to creating a thriving and successful learning environment. (And needless to say, I did not distribute red markers for name cards again).

Over the ensuing years, I continued to develop my cultural intelligence, both through proactive self-development and learning from my mistakes, and feedback from my students suggests I have successfully created open, tolerant, learning environments that respect different cultures.

Here are my five practical tips for building cultural intelligence to create a thriving diverse classroom.

1. Reflect on Your Own Background

Developing cultural intelligence starts with self-reflection. Understanding your own cultural background, values, and beliefs is crucial in recognizing how they influence your perceptions and interactions with others.

Begin by examining your cultural identity. Reflect on how your upbringing, class, nationality, education, and community have influenced your worldview. This self-awareness helps you understand the lens through which you view the world and interact with others.

For instance, reflecting on my own educational background helps me to understand why I might have totally different interpretations of major world events compared to someone who was taught history differently. (For example, thanks to the British history curriculum, I tend to view the Second World War through the lens of “good” Allies vs. evil Hitler, while my Chinese students and colleagues are more likely to see it as centering on conflict between China and Japan).

Understanding how where I’ve come from shapes my own perspectives helps me approach conversations with a more open-minded attitude. Rather than assuming someone is wrong or lacks knowledge, I can start from the assumption that they have been exposed to different knowledge and belief systems.

2. Know Your Biases

We all have biases, conscious or unconscious, that affect our judgments and behaviors. Recognizing and addressing these biases is a critical step in developing cultural intelligence.

Start by educating yourself about common biases, such as stereotypes, prejudices, and microaggressions (i.e. subtle, often unintentional, discriminatory comments or behaviors). Reflect on situations where you might have made assumptions about others based on their cultural background. Consider how these biases might influence your interactions with students and colleagues.

An obvious example of this is the stereotype that Chinese students love and excel in mathematics but struggle with critical thinking. In my experience, while many love math, some hate the subject, and Chinese students are just as capable of critical thinking as their non-Chinese peers when given the opportunity.

Consciously pushing back against this stereotype creates space for students’ individual personalities and strengths to come forward.

3. Get Out of Your Comfort Zone

Understanding your background and biases can allow you to approach others from a more self-aware and open-minded position. However, developing practical, specific knowledge about other cultures (which in turn helps avoid mistakes like my red pen debacle!) is best done by getting out of your comfort zone and immersing yourself in cultures different from your own outside of the classroom.

In my experience, the best way to do this sustainably and consistently is to find something you enjoy, but do it with people from different backgrounds. For me that’s joining sports clubs, but it could be going to a weekly cooking class, finding a book club, or joining a choir. Through regularly talking to people from a different culture and forming genuine friendships, you learn things you would not otherwise get exposed to (including things that aren’t often found in books and articles about how to adapt to particular cultural settings).

Likewise, most faculty educated in Western academic institutions are primarily exposed to literature produced in Western academic institutions. Make an effort to read more diverse literature, and put it on your syllabus. When students see authors or case studies from their own culture alongside those from others, they feel more included. And, at the same time you expand your own intellectual horizons.

4. Practice Empathy

Cultural intelligence does not necessarily mean constantly adapting your own behavior to fit in to another culture (more on this below), but it does mean consistently practicing empathy, i.e. making an effort to understand and share the feelings and experiences of others.

Put in the work to understand why students from different cultural backgrounds may approach questions, tasks, and problems in a certain way. For example, I found that many of my Chinese first year students struggled with writing an essay conclusion that did not contain some kind of vague expression of hope for a better world, even when this was completely irrelevant to the question being posed.

At first, I was confused and frustrated (“why aren’t they reading my carefully-curated grading rubrics?!”). However, once I took the time to understand the style of writing that is valued in China’s gaokao (university entrance exams), I realized my students had spent their whole educational lives being told that they should include such expressions in their essay writing. (I even bought some gaokao preparation revision books to see what kinds of things they’d been taught.)

I started to understand that for my first year students, writing an essay that did not include this felt strange, and it was hard for them to shake off the idea that something would be missing or they would get a poor grade.

As a result, I spent much more class time explaining the importance of genre and writing for a specific target audience, and showing my students how different communication styles were valued in different contexts. This empathy resulted in happier students who themselves became better, more culturally aware communicators.

5. Know When (And When Not) to Adapt

Cultural intelligence involves knowing when to adapt behavior to different cultural contexts and when to maintain authenticity. My general rule is to adapt if (1) it is conducive to effective learning and/or a respectful environment, and (2) it does not involve compromising my core values or losing my authenticity.

To give an example of when not to adapt, some of my students (both international and Chinese) may enter university with conservative ideas or unconscious biases regarding gender roles, depending on their background. This can affect their group work, for example, with male students more likely to be chosen for leadership roles.

As someone who strongly believes in equal opportunities for people of all genders, I make a conscious effort to counteract this tendency rather than go along with my students’ existing cultural norms (such as by randomly choosing the group leader myself, or by appointing the youngest or oldest student – regardless of gender – to take the lead).

However, I do make a conscious effort to alter my communication style, for instance by speaking in a more direct way that avoids colloquial language. This caters to the needs of diverse students but does not compromise any of my core values. Likewise, returning to the red pen example, it does not compromise my authenticity or values to understand and respect the fact that Chinese students do not want to write their names in red ink, so I now simply make the effort to remember not to give out red pens for name cards.

By balancing adaptation with authenticity, you can create a classroom environment that respects and values diversity while staying true to your educational philosophy.

Conclusion

Developing cultural intelligence is a continuous journey that requires self-reflection, learning from mistakes, and practice. By reflecting on your own background, recognizing your biases, stepping out of your comfort zone, practicing openness and empathy, and knowing when to adapt, you can create a thriving, diverse classroom.

Moreover, embracing cultural intelligence not only enhances your teaching but also empowers your students – through learning from your example – to navigate and succeed in an increasingly diverse world.

Would this article be helpful for someone you know? Click the links below to share ⬇

Check out more tips for academic success by following Discovery Hub on social media ⬇

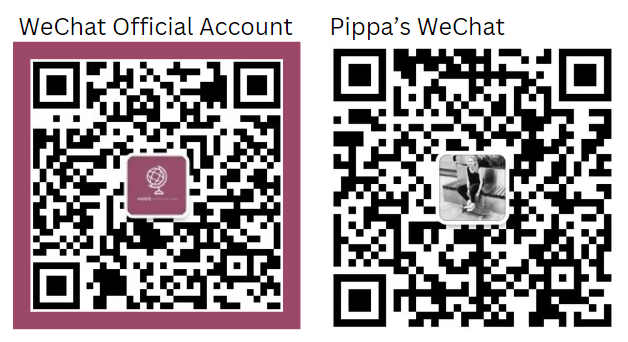

Follow Discovery Hub’s Official Account or connect with Pippa on WeChat ⬇

Copyright @ 2024 Discovery Hub Educational Consulting (Suzhou) Ltd 探索枢纽教育咨询(苏州)有限公司.